In 1921, a young Sandy Low was sent away from his home in Kohala to attend school in Connecticut. He never returned to Hawaii. But he gave his aloha spirit, his appreciation of Hawaiian music, and most importantly, his love of the sea, to his son, Sam Low, who was raised on Martha’s Vineyard off Cape Cod. Sam Low took all that his father had given him to heart, and returned to Hawaii to become an ocean voyager.

Transcript

Clorinda Lucas, who I guess you knew, ‘cause you lived in Niu, right?

Right; she’s your aunt.

She’s my aunt; she’s my father’s sister. After my dad graduated from art school, he had a studio in New York, I think it was on 23rd Street, little loft. And Clorinda showed up. And here’s a Stutz Bearcat parked in front of my father’s studio. A Stutz; it’s like a Ferrari. So, she goes up the winding staircase, gets into this studio, and they exchanged pleasantries. And she says, Oh, well, Sandy, whose beautiful car is that? And my father looked at her and said, Oh, it’s mine. Yours? You know, of course, that can’t be. He had no money at all. And he said, Oh, well, all right, my girlfriend loaned to me. Me, or somebody. And so, he was just popular. He just had that kind of magnetism, and I think he made his way that way.

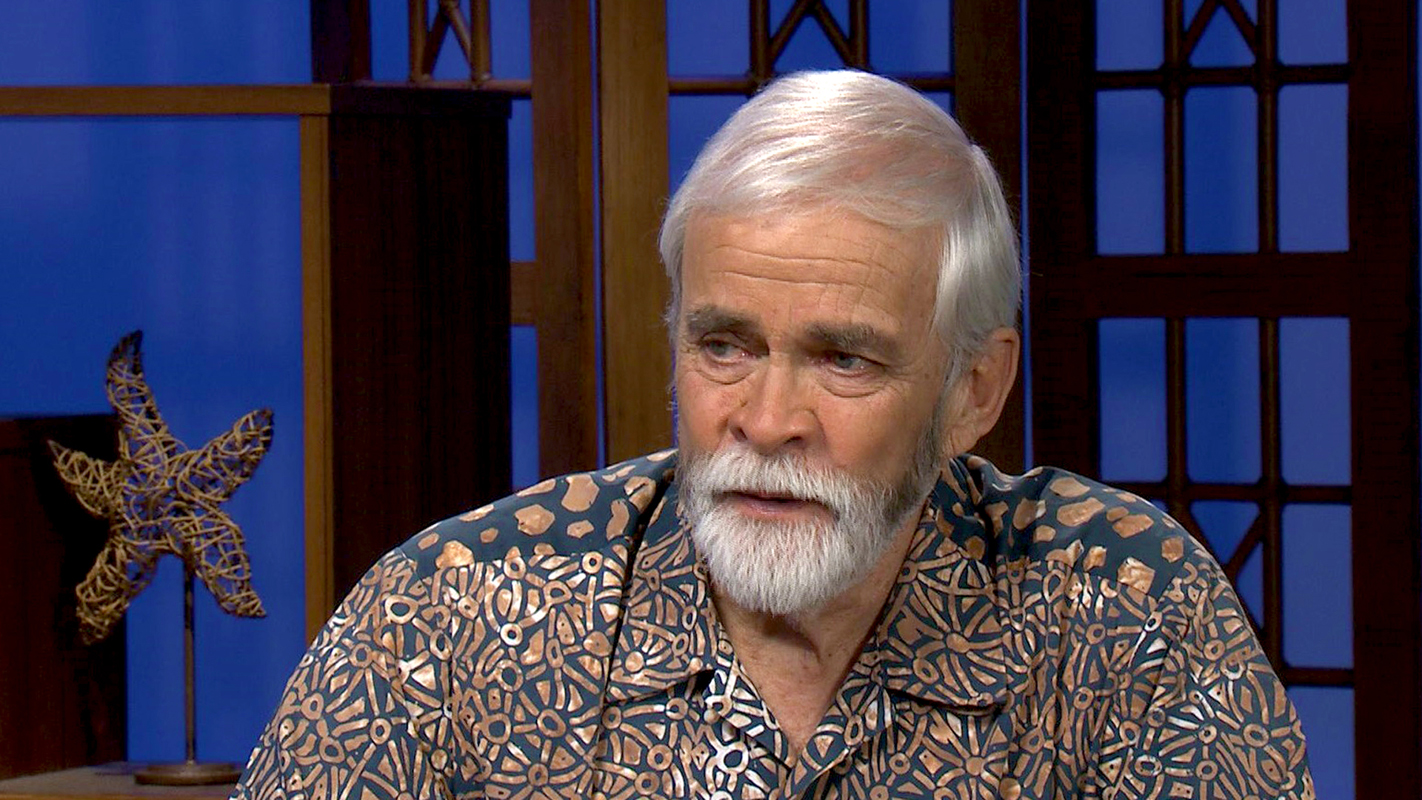

Sam Low was born in New Britain, Connecticut to a half-Hawaiian father and Caucasian mother. He grew up in New England, and has spent most of his life there, yet identifies as a Native Hawaiian as strongly as he does with being a Connecticut Yankee. Sam Low, next on Long Story Short.

Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox is Hawaii’s first weekly television program produced and broadcast in high definition.

Aloha mai kakou. I’m Leslie Wilcox. Sanford Low, Jr., or Sam as he’s called, may be best known in Hawaii as a sailor and documentarian aboard the Polynesian voyaging canoe Hokulea, and more recently, the author of a book, Hawaiki Rising, about Hokulea, his cousin Nainoa Thompson, and the Hawaiian renaissance. Although Sam’s father left Hawaii way back in 1920 as a sixteen- year-old boy and never returned, he stayed closely connected to Hawaiian ways throughout his life. This gave Sam his grounding in Hawaiian culture long before his first trip to Hawaii.

You are a quarter Hawaiian, three-quarters Caucasian.

Yup.

And how much do you pull Hawaiian?

How much do I pull it, or how much do I feel Hawaiian?

Yes.

How much do I feel Hawaiian. More and more, and more, and more. I grew up in a Yankee community, Connecticut Yankees. My grandfather was an Industrialist; he worked at Stanley Works. He was president of Stanley Tools. He lived in New Britain, Connecticut, and they had a summer place in Martha’s Vineyard. My father was kind of an oddball in that Yankee family. He was an artist, he was a Bohemian. He had run away from prep school. He was sent by his father, Eben Parker Rawhide Ben Low, to luna school.

From?

From Kohala. And he had a wonderful time on the Lurline, where he played guitar and formed a band. He had a great time going across on the Transcontinental Railroad. Really enjoyed his travel. And then, he got to this prep school, and everybody was in coats and ties, and formal, and he felt completely at sea, completely lost. So, he played football; he was a great athlete. Played football, halfback in bare feet.

In the cold?

Well, yeah. M-hm; yeah. Football is generally in the fall, and you might have a snowstorm. So, when football was over, he was so homesick, he was so bereft of that kind of aloha spirit that he’d gotten used to, that he jumped a train and went to Long Island, where his sister lived.

I thought you were gonna say he jumped a train to go back to Hawaii. But he actually never went back to Hawaii as long as he lived.

I know. And that’s always strange. He jumped a train; he went to his sister, who was married to a Haole guy. They had a farm; I don’t know too much about that. But his sister died very shortly thereafter, and it’s very hard to piece together all of that story. I didn’t sit at his knee and ask him, as I should. But what I know is, he was a stevedore for a while. He shipped out; he was quartermaster, went up and down from New York, Boston, to South America and back. He always had this dream of being a cartoonist, and he was always sketching. He was an artist from the beginning, and he had this dream of being an artist. So, somehow, without a high school education, with just three months of high school, he got accepted at the Museum School in Boston, which is one of the premier art schools. And he spent, I think, three years there, graduated, and then went to New York, became a commercial artist, and then met my mother. He was handsome, he was Hawaiian, he was athletic, he was beautiful to look at.

Was it a plus to be Hawaiian in that society then?

In those days, definitely. I mean, it was such a romantic thing. Denizens of the sea, surfers. And in New York in particular, there were many bars that Hawaiians would hang out at. It was a very active scene. So, he was kind of an anomaly in that all-Haole society, all those blonds named Bart. And the story of their meeting; he was invited to one of these parties out in South Hampton on Long Island. And they had in those days these speed boats, Garwood speed boats, long, mahogany, big powerful engines. And they would tow an aquaplane behind it, which is just basically like a surfboard with a rope attached to the boat. And the swains, the Haole swains, barts with their blond hair, would get up on it. There was a rope, and you’d hang onto the rope, and you’d go back and forth across the lake. You know. And [CLAPS HANDS] everybody would clap, you know. Bart; all right! So, my father was asked, Well, would you like to try this, Sandy? And so he said, Well, sure. So, he got on it, and he went back and forth too, only he was standing on his head.

And holding onto the rope?

No rope; just standing on his head.

Wow.

I mean, he was a surfer, so that was no big deal. This thing is totally stable; he’s just standing on his head and go back and forth. Which excited the interest of a lot of the young women there, including my mother, who was an artist as well. So, they had that in common. And they got together, and eventually married, not after certain tests were administered, let’s say.

Was there opposition in the family to his marrying her?

I think that she was being squired around by a young man named Salton Stahl, which was a kind very prosperous Hartford, Connecticut family. And I think probably my gram and grandpa were a little astonished when she brought this Hawaiian guy back, who had no money at all. His father had lost all his money. That’s one reason why he perhaps didn’t go home. And they were really good people, but on the other hand, they were a little suspicious of this artist Hawaiian guy. Was he marrying her for money, or what. And so, they made a deal. My mother and her mother would go on the grand tour; they would take off for three months, they would travel throughout Europe, and if Ginny Low, Ginny Hart in those days, if she came back and still wanted to marry him, it was a done deal. But there was gonna be a cooling off period. And I still have all their letters in a little box, and I hope to do something with that someday. But all these wonderful letters going back and forth. And when they got back, Mom said, I want to marry him. They said, Okay. And he was accepted definitely into the family, and they realized what a good thing they’d done.

Her parents were true to their word.

Yes, they were.

You know, he must have felt kind of lost. I mean, he’s on the East Coast, and unhappy at school. Goes to visit his sister, she passes away.

Right.

No family, no money.

Right.

I wonder, did you ever know what he was thinking?

I don’t know. But there’s another story. I mean, people seemed to gravitate to him. I mean, I think the Hawaiian part of him was that outgoingness. You know, the looking at somebody and seeing the positive, seeing the aloha, welcoming that person into his embrace, both real and spiritual. And I think that stood him in good stead; it opened paths for him.

He probably would have been okay everywhere he went, then.

I think so. Yeah.

Wow. And he and your mom enjoyed a long, happy marriage?

Yes; right to the end. Yeah.

Sam Low’s father had been a waterman growing up in Hawaii. Living close to the Atlantic Ocean, he was able to share his love of the ocean with his son. Sam Low grew up with perhaps as much Hawaiian culture as was possible for a boy growing up in New England in the 1940s and 50s.

My Haole family, the Harts, were very family-oriented. The concept of ohana, which wouldn’t have been expressed that way, was very strong among them. And they lived in New Britain, Connecticut, which is the hardware capitol of the world, but they lived in a family neighborhood. When I grew up, all around me lived aunts, uncles, and cousins. So, it was quite a bit like you would grow up in Hawaii. And then, on Martha’s Vineyard, which is this tiny island off Cape Cod, my great-grandfather bought a farm, and then he subdivided it and gave lots to all of his children, and then, their kids moved in. So, I grew up as well in kind of an ohana neighborhood. And I still do; that’s where I live, and that’s what I love about it, we’re all family. And I think that for my father, when he discovered that family that had those tight connections, he started to feel really at home, started to put his roots down.

Did he keep in touch with family in Kohala?

Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, in Kohala or on Oahu. In fact, in those days, Hawaiians were peregrinating everywhere. And people in his family, they would go to Stowe to ski; Stowe, Vermont.

So, it wasn’t as if he didn’t see people from his family.

No; they would come and visit. You know, probably once a year, as a young kid growing up, there would be this hoard of people coming in, all jabbering away and having a wonderful time. And then there would be hula, and there would be singing. So I was exposed to that as a kid. And I think that really helped my father as well, to have family come and visit once a year.

So, may I ask; just why didn’t he go back? He could have.

What he told me was that he left, he started a career, he started a marriage, he started a family. And time passed. So, when he started to think about going back maybe in the 40s and 50s, his father died in 1954, and he did want to go back and see him. By that time, what he told me was that Hawaii had changed so much, that he really wanted to keep his memories of the way it was when he left.

I see.

And then, Martha’s Vineyard was his saving; it saved him. Because he went there for the whole summer, and he would fish, and he would get opihi. And uh, you know, he became famous for getting these little periwinkles off the rocks and taking them and [SLURPS] eating them.

Did anybody else do that?

They did, eventually. And these Yankees started eating sashimi and raw fish, and periwinkles, and he had a major impact on their lives.

Did he do anything luau-related?

Yes.

Anything from home that way?

Yes; yes. Well, uh, he started a luau in this community on Martha’s Vineyard called Harthaven, actually, and my middle name is Hart. He married into the Hart family. He came up with the idea for a luau, but it became a clambake. Because that was what they were used to. And so, the clambake became an annual event that he presided over. And so, he brought this kind of sense of— and the way they had it, you know, Yankees would normally hire somebody to put on a clambake. No, no, no. Everybody’s gotta come, everybody’s gotta help with the fish, and everybody’s gotta help with the oysters and the clams. Everybody’s gotta build the pit, everybody has to clean up. And so, he created this kind of cement that brought everybody together. And I think that was his spirit as well.

And you shared his attraction for the ocean.

Yeah.

So, you were a part-Hawaiian who grew up on an island, who loved the water, but it was not the Pacific Ocean.

No.

And you never lived in Hawaii as a kid.

No. No, but from very early on, actually, my father said, Well, Son, there’s only one way for you to learn how to swim. I gotta take you out on the boat and throw you overboard. My mother said, No, you’re not gonna do that, Sandy. And so, she took me to the beach and did the normal thing of, you know, letting me go out ‘til I touch, teaching me how to float, and all that sort of stuff. And I was given a rowboat when I was a kid, and I rowed up and down. We had a harbor there, and I rowed up and down the harbor, you know, hours. And then, one of my uncles had a little one and a half horsepower Evinrude outboard motor, and so that went on the back of the rowboat, and I would go [IMITATES ENGINE].

[CHUCKLE] How old were you then?

I was probably eight.

Wow.

And eventually, a rule was passed that I could only do that between ten and noon.

Because you were so irritating?

Oh, god, these people were out there trying to, you know, have their cocktails at five. [IMITATES OUTBOARD MOTOR]

[CHUCKLE]

But eventually, I acquired larger boats, I got into scuba diving, did a lot of wreck diving. And I was in the water all the time. And that came from my father, really, just emulating him.

Sam Low made his first trip to Hawaii in 1964. It turned out to be a bittersweet trip, but opened the door to a part of himself that he had previously only known through his father.

The first time I came to Hawaii was as a Navy officer.

How old were you then?

Well, how old was I? I must have been twenty.

So, first time here when you’re twenty.

Yeah. And I was in ROTC. I wanted to serve my country, I wanted to be on a ship. If I’m gonna serve my country, I better be on a ship. And it was a wonderful experience. It was the beginning of the Vietnam War. I requested and got Pearl Harbor, ‘cause that was my chance to come see my country, really, my islands, my people. I was going to drive across country in a Volkswagen. And then, I was gonna have the Volkswagen shipped to Pearl Harbor. And so, before I left, I had my bags in the Volkswagen, and my father and I embraced. And he said, Son, I’m gonna go back to Hawaii. I’ve not gone back, I didn’t really want to, but you’re gonna be there and I do want to see my family, and so, I will see you there. And we embraced. He died that night. I was a day down the road, and I got the word on the phone.

Oh; wow, that’s so hard. How old was he?

He was young; he was fifty-nine. After he passed, the Navy gave me two months compassionate leave to come back, and we buried him. I told my mother that I could be reassigned to a base on the East Coast, and the Navy would do that. And she said, No, your path is set.

And it was, wasn’t it?

It was; yeah. She said, You’re on your way to your father’s land, and you should continue. She was wonderful about that. I shipped out immediately to Subic Bay, and then we were in the Gulf of Tonkin, and then the Vietnam War started, and I felt it was my duty to be there. So, when we first came back from a deployment about a year over there, I immediately volunteered to go back. And I did that. So, my experience, my first experience here in Hawaii as a naval officer, I was mostly in service at sea. But I did get to meet my family, Clorinda Lucas, who is my father’s sister. And I sensed in her this deep Hawaiian spirit. I don’t know if you knew her.

I didn’t know her; I grew up hearing about her.

Yeah.

And she’s passed away now, of course.

Yeah. Well, first off, she lived in Niu, and she lived on Halemaumau Street, at the head of a little entrance into the valley. So, there were all these little houses around, down below, and then you drove up this road. It went from uh, asphalt to dirt. And then, you got into this valley, and there was a pasture there with horses, and there were two or three houses. And that was her place. And so, it became almost rural. You went from Honolulu, you went to Niu, you went to this subdivision, and then, all of a sudden you were back in—you could be anywhere. You could be on the Big Island. And all around her lived her children. So, this was a real ohana compound, and I recognized the similarity there between how I grew up. But we didn’t have horses. And if you looked up the valley, here were these beautiful mountains. And Clorinda was the ohi nui; she was the matriarch, she was in charge. And everybody paid attention to her. She had a very benevolent, loving attitude, but when she said something was gonna happen, that’s the way it was. So, I’d not seen a matriarch before like, quite, and that was wonderful. And then, one of the things I experienced almost immediately is that particularly on Sundays, Saturdays and Sundays, there would be people coming and knocking the door. They weren’t announced, they didn’t know that they were gonna show up, but it was kind of like open house. And Hawaiians from all walks of life would come, some bearing gifts, some with problems, some with questions, some with something needed to be solved. And so, Clorinda had that kind of alii outreach. And that was new. So, I felt, I think, with her for the first time that sense of aloha, that sense of benevolence, that sense of taking care of other people. She was a famous social worker. Her daughter married Myron Pinky Thompson, who was equally caring of his people.

The husband was a social worker.

Yes.

Of Laura, the daughter of Clorinda.

Right; right. Clorinda’s daughter Laura married Pinky Thompson, Myron Pinky Thompson, and he was a wounded veteran. Went ashore in Normandy, was a scout, was hit by a sniper, sent back, went to school on the East Coast, Colby College due to fortuitous circumstance, and then returned to Hawaii and dedicated his life entirely to the Hawaiian people. He was a social worker from day one. He was the head of the Queen Liliuokalani Trust. He was an advisor to Governor Burns, very close with the Hawaiian delegation, and pretty much dedicated his life to helping Hawaiians understand their proud heritage. And that’s how he really got involved with the Polynesian Voyaging Society, as well.

He was a very humble man, too. I remember getting a tire blow out on Kalanianaole Highway, and guess who stopped to change my tire?

Pinky.

Yes.

Yeah.

Changed it, and left.

He would do that. Yeah. So, you know, having the chance to come to Hawaii and to be involved in that community, the Lucas family and the Thompson family, and Low, you know, it was an immersion course in kind of the spirit that you take care of each other.

Your aunt must have curious about you, too. Even though she’d visited your father, she must have been interested in getting to know you as an adult.

I had a terrible reputation. I was a spoiled brat when I grew up.

Were you, really?

Yeah; I’m afraid.

Were you obnoxious?

I’m afraid I probably was.

So, felt very entitled?

Yes. I was an only child, and so, the report came back. She saw me, but the report came back that, you know, Boy, Sandy and Ginny have this brat for a kid. And I think I had to overcome that when I got out there, and I can’t say whether I did or I didn’t, but I can say that Clorinda, you know, gave me this immense hug every day, either physically or just spiritually, and I felt her aloha envelope me immediately. And so, that that drew me into wanting to know more about, what’s this about, what’s this quarter of me that is different than my Yankee part.

How much had you wondered about that?

Probably when I was growing up in New England, not so much.

And could people tell you were part-Hawaiian?

Well, they knew I was different. I would freely, you know, offer that, because I thought it was cool. Growing up as a young man, you know, I’m six or seven, of course, I wanted to be a cowboy. And my grandfather was a cowboy, and so, I was very curious about that. My father would tell stories about going up into the valleys and bringing back a pig, and hunting.

And a grandfather named Rawhide Ben. I mean, how exciting is that?

Right; that was pretty amazing. I did want to come back, and I did want to see that. You know, I was very curious about it. But it was really only when I finally did come back, you know, kind of carrying my father’s spirit with me, that I recognized that I was really coming back for him and me. And that gave it a different dimension.

What a tumultuous entrance. I mean, to have your father pass away, and then you’re caught up in the events leading to the Vietnam War.

Yeah.

It must have been a tough time for you.

Yeah. It was. But as I say, having that kind of family, Clorinda and Pinky, and Laura, made it feel very secure, very warm.

Did Laura make her trademark beef stew for you?

Yes. Yes, she did. Now that you mention it, absolutely; yeah. Which was kind of uh, familiar.

You’ve described this lovely community where you lived, where you were surrounded by family. As we all know, family is a blessing, and occasionally it’s a curse. What’s it like living always with family that, you know, you can’t go home and be away at times.

I think it’s wonderful. It’s that bond that you can’t break, really. So, you will always have a disagreement or a flash of anger, or something. But if you live in an ohana, whether it be a Haole one or a Hawaiian one, you always know that you can come back and that the door will open, and that you can go through hooponopono and be back together again. And I love where I live on Martha’s Vineyard. I love that probably sixty, seventy percent of the people who live there are family, they’re cousins. And there’s kind of a circle, dirt circle, and if I set out to go for my walk, unless I tell people I’m walking and I gotta keep going, it can take me forty minutes to cover half a mile, because there are people to talk to.

It is a community.

It is a community; it really is a community. And I loved growing up in that. So, I’m very happy to have cousins all around, both here and in Harthaven.

Sam Low did not grow up in Hawaii, but his love of the sea and family have always connected him to his Hawaiian culture, and eventually, to Hokulea, the double-hulled Hawaiian voyaging canoe that is guided only by the elements of nature. Mahalo to Sam Low from Martha’s Vineyard on the East Coast for sharing his family stories with us. And mahalo to you for joining us. For PBS Hawaii and Long Story Short, I’m Leslie Wilcox. A hui hou.

For audio and written transcripts of all episodes of Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, visit PBSHawaii.org. To download free podcasts of Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, go to the Apple iTunes Store or visit PBSHawaii.org.

In the 1995 voyage, we went from Tahiti to Hawaii, and I was on a Swan, which is a luxurious kind of racing yacht. And that was the hardest voyage I’ve ever been on, because it’s a mono hull, and as soon as you get out there, it goes, pfft, like that, you know. And so, you’re always working at thirty degrees. You’re always struggling. And then, pow!

That’s not luxury.

No. Nice when it’s anchored. And then, when I got to voyage on Hokulea, having that experience, I thought, Oh, god, this is gonna be tough, we’re going to be out in the open, and whatever. But Hokulea … it’s so graceful, and she doesn’t tilt. You know, she’s got two hulls. She goes out, the wind comes, she takes a set. And she goes. And those beautiful manu’s just cleave the ocean. And so, in the most difficult of weather, with all the sails down, you know, you just hunker down, and she’s just floating over it like a duck.

[END]