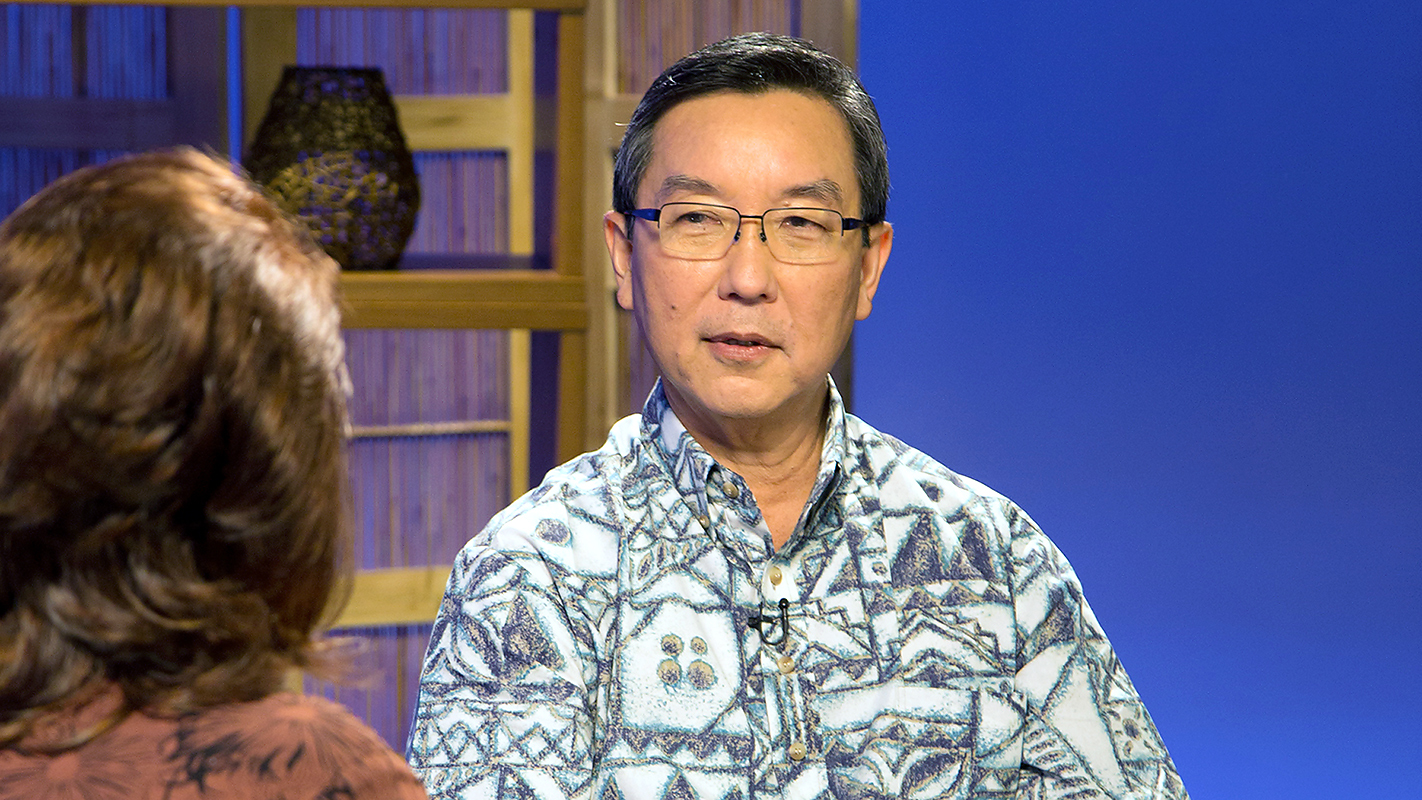

Colbert Matsumoto grew up on Lanai when it was a pineapple plantation employing both his father and mother. He didn’t set foot on the Continent until he was a college freshman. And he grew up to become an attorney, insurance company executive and business and community leader in Hawaii. Like many successful people, he had some misgivings and missteps along the way. On the next LONG STORY SHORT (Tues., July 7, 7:30 pm), Matsumoto humbly recalls his journey. And he tells of a test of his courage, as court-appointed master overseeing the dealings of then-Bishop Estate.

This program is available in high-definition and will be rebroadcast on Wed.,

July 8 at 11:00 pm and Sun., July 12 at 4:00 pm.

Transcript

You said your dad was a 442 vet, so that means he qualified for the GI Bill. He could have gone to college, but you’re saying he did not?

Yeah; my dad unfortunately, as soon as he came back from Europe and returned to Lanai, his father died unexpectedly. And so, my father, because he was the youngest in the household, and his siblings had all left the island already, stayed on Lanai to take care of his mother. So, he was from a generation that had this Japanese value of oyako-ko imbued in him. And so, I think that, you know, basically he said, It’s my responsibility to take care of my mother.

Do you think he ever regretted that choice?

No. If I he did, I never heard him articulate it. But I think that that was probably why he expected my brother and me to go to college.

That sense of doing what’s right was passed on from father to son. Born and raised on Lanai, Colbert Matsumoto would remember his dad’s leadership by example when he took on some of the most powerful people in Hawaii, and helped reshape the multi-billion-dollar Bishop Estate. Colbert Matsumoto, next, on Long Story Short.

Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox is Hawaii’s first weekly television program produced and broadcast in high definition.

Aloha mai kakou. Colbert Matsumoto went from plantation life on Lanai to become a business and community leader in Honolulu. He’s chairman of Island Insurance. Matsumoto’s life and career have been driven by a desire to impact lives, a motivation he’d seen his parents put into action as workers on Lanai’s pineapple plantation.

I grew up in a time when—I like to call it the Golden Period of the Plantations in Hawaii. Life was really nice growing up on Lanai. You know, our family, I think, you know, we had a comfortable lifestyle. We didn’t have a lot of extravagance, but you know, we had a TV set, you know, I was in the Boy Scouts. You know, my parents were members of the PTA, you know, we went to church on Sundays. And so, it was a nice place to grow up in. And so, as I look back on it, you know, I realize how almost idyllic it was to grow up in a place like that. But when I was growing up there, I couldn’t wait to leave.

Because it was too small a town, people all knew each other’s business, maybe?

Yeah; it was confining. I grew up in a community of twenty-five hundred people. Oh, there were many occasions when, you know, I would get into mischief as a little kid on one side of the town, and by the time I got home, my mom would know all about it. You know, and so, yeah; it was hard to remain anonymous.

When you said you couldn’t wait to get away, were there other things besides getting ratted on for mischief?

Oh, yeah. Growing up, we had a TV set, and I would watch shows about other places, and I always longed for the opportunity to experience some of the things that I saw on the TV programs. Because I didn’t get away from Lanai very much. I had never had the opportunity to visit the mainland until I went to college. And so, I felt somewhat isolated and confined as I grew older, and wanted to have the opportunity to experience different things.

The main employer on the island at that time was Dole; right?

Right.

And did your parents work for Dole?

Yeah; both my parents worked for Dole, as my grandparents also. Pretty much everybody on the island worked for Dole, unless you worked for the State or the County, or some of the retail establishments in the town.

There are drawbacks to company town, obviously, when you’re held in their thrall; they’re the main gig—

Right.

–for employment.

Well, you know, I think that, yeah, the only jobs that were available were on the plantation. Which is why, you know, growing up, we all knew that once we graduated, we were expected to leave the island. Because there were no opportunities for young people after they graduated from high school on Lanai.

Which your parents had that expectation of; right?

Oh, yeah; the parents. But you know, it was also the economic reality of the island.

I mean, were you concerned? What am I gonna do? How am I gonna make it?

No. You know, I think my parents always raised me with the expectation that I was supposed to go to college. They themselves had not gone to college, so they didn’t care which college, or what I studied. You know, they just wanted me to go to college and graduate from college.

Did they explicitly give you lessons of life?

They did, you know, in different ways. So, you know, they would basically try to teach me certain values. But then, they also, I think, taught me a lot just by their example.

Your father, for example; what did he teach you? What did you come away with?

One of the things that he was heavily involved in was with the ILWU. Because the union figured very significantly in our community. So, my father would share with me some of the stories of the struggles that the union and the employees had to go through in the beginning. ‘Cause he was a 442 veteran, and so when he came back, one of the things that he and, you know, people of his generation were struggling for were not just economic justice, but also social reforms in the community. So, the union, the ILWU was very significant in, I think, bringing about some changes back on the plantation. ‘Cause many of them didn’t have the opportunity to own their homes. So, one of the things that they struggled for was to have the opportunity to buy their own homes, which many of the workers did.

Under your dad’s tenure?

Yeah; during the time that he was involved with the ILWU.

What was your mother like? What is she like? Because, you know, she’s still with us.

Right. My mother was a strong woman. You know, she made sure that my brother and I kept out of trouble, which she didn’t always succeed at.

But she always found out.

Yeah; she found out. But she was a stickler for the rules, and you know, she really had a strong sense of fairness, of right and wrong. And I think that that enabled her to go from being a pineapple picker to one of the first female, wahine lunas on the plantation.

What was that like? So, did she boss men around?

No; she usually headed, you know, gangs of women who were ipicking pineapple for the plantation.

Oh, that’s wonderful; a wahine luna.

Right. But that wasn’t until, you know, the late 70s, when equal rights became more of an issue for women.

So, it sounds like both of your parents challenged; challenged for more fairness, for equity.

Right. I think that, you know, that generation, they were second generation Japanese Americans. That generation really was focused on bringing about social change for the benefit of the community. And so, both of them made contributions in various ways through the activities that they were involved in and volunteered in. And they were among many in the community that were also, you know, engaged in those kinds of efforts on behalf of the group, as opposed to just for their own personal benefit.

Colbert Matsumoto was valedictorian of his high school class on Lanai. He went on to college in the Bay Area, and graduated from law school at the University of California at Berkeley. He wanted to be a lawyer to have an impact on society.

When I went up to college, it was the first time I was up on the mainland. So, it was a total culture shock for me. I had never been on the mainland before, I had never seen an urban environment like that. So, was definitely an eye-opening experience.

How was your college experience? What’d you decide you were gonna do with your life? Did you decide then?

Yeah; I had gone to college with the intent of becoming a high school social studies teacher. So, that was my objective going in. About halfway through, I came home for a summer and worked at a warehouse on a nightshift crew, and there were three other guys that were working on the crew that had already graduated from UH in education. One had a master’s degree, the other two had fifth-year certificates, and none of them could find jobs with the DOE.

That’s right. I remember that was the time of a teacher surplus.

So, I figured I needed to find something else. And that’s when I decided, Well, I guess I’ll try applying to law school, which is what I ended up doing.

Any particular reason?

Well, you know, I had never met a lawyer before. I had never been in a courtroom, or knew anything about what the practice of law was. At the time, you know, I just knew that lawyers went to court. Perry Mason, The Defenders; those were my images of lawyers. And I thought, you know, lawyers made a lot of money, and didn’t have to work hard.

[CHUCKLE]

And so, I thought that, Okay, maybe that would be a good profession to get into. But I also knew that lawyers had the ability to bring about change, that they had a certain knowledge base that allowed for an advocacy of different ideas. And so, I thought that by becoming a lawyer, I would be able to have an impact in terms of society. Because, you know, I grew up in the 60s, so it was a time of a lot of social change; the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War and the anti-war movement. It was also a time when, you know, the environmental movement first started to get started. And so, there was a lot of idealism, I think, with my generation. And so, I looked at, you know, practicing law as being an opportunity to become more of a contributor to the kinds of social changes that were taking place in society.

You were used to being a really smart guy in all your classes up ‘til now. Now, in law school, everyone was probably the smartest in the class they came from before.

Right.

What was that like?

It was very intimidating. Like I said, I had no clue what being a lawyer was all about. And so, I almost flunked my first semester of law school. Because I thought a contract was a piece of paper that, you know, you put an agreement on. I didn’t realize that it was a legal concept that had, you know, certain components to it. And so, the concepts associated with law were so foreign to me, so I had a hard time grasping a lot of that when I first went to law school.

Do you think maybe part of it was because you were used to more of a handshake, and your word was good, and it was sort of uncomplicated on Lanai?

No, I think I was pretty much just naïve and clueless about what I had elected to pursue in law. So, fortunately, I had a professor who was very sympathetic, and I had some fellow classmates that were very supportive and encouraging. And so, I stuck it out, and managed to do okay.

Colbert Matsumoto did something quite unusual after he passed the Bar Exam and was qualified to practice law. He embarked on a six-month journey that continues to inform his life.

I entered a Zen monastery. So, I shaved my head, and then went into this Zen monastery and trained.

Where was it?

It was in Kalihi Valley. So, it was Chozen-ji. It’s a Rinzai Zen temple. And I had heard about the teacher there, Tanouye Tenshin Rotaishi, who was an accomplished martial artist, but also a Zen teacher. And so, I had trained in the martial arts when I was a kid growing up, and so, you know, I had an interest in it. But I had also realized that Zen was the philosophical underpinnings of Japanese martial arts and so, I wanted to learn more about that. And so, that’s why I asked him if I could, you know, train with him at his temple.

And what did you learn?

You know, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. It was a very rigorous and arduous kind of training, physically demanding training that I went through while I was there. But it was also psychologically very stressful and difficult.

When you said arduous, I don’t really know what that means in terms of meditation or Zen studies.

We would get up at like, you know, four-thirty in the morning. We would sit in meditation for hour and a half from five-thirty. And then, we would have breakfast and then, we would do martial arts training from eight to ten in the morning, and then we would have to work out in the gardens or do some construction activity. And then, in the afternoon, you know, we would bathe, and then we would go through another period of intense meditation, and then we would do martial arts training from seven-thirty to like, ten o’clock at night. And you know, it was just physically very demanding. And I mean, I lost a lot of weight while I was going through that, and it was very tough, both physically and psychologically.

And was it meant to reduce you to who you really are, to take away the external stuff?

Right. Basically, the training had a lot to do with, you know, freeing you from your dependence on the kinds of things that you grow up with, thinking that these are real things that you can hang onto in terms of defining who you are, and defining your life and how you lead your life. There definitely are gonna be times when you’re not gonna be able to overcome certain things. But you have to try. So, it’s more about the effort and how it transforms you as a person, by taking on that challenge.

That’s interesting, ‘cause as a lawyer, I think you’re pretty goal-oriented. But you’re saying you learned how to accept that the effort is the main point.

Right. I think, you know, as human beings, you know, we have the capacity to continue to evolve and change, and grow. But you have to make the effort at it, and you have to be willing to take the risk associated with experiencing those kinds of changes in your life.

Following his Zen training, Colbert Matsumoto went into business as a solo law practitioner. He shared office space with a man who would become governor, Ben Cayetano. Later, he joined the law firm of the late Wallace Fujiyama, one of Hawaii’s finest trial lawyers. Yet, Matsumoto says his early years in law were hardly a success.

The first thing I did was, I hung my shingle and tried to practice law on my own for two years, which was a disaster.

Why?

Because I wasn’t prepared. You know, law school doesn’t really prepare you to practice law.

To run a business; is that the part of it that got you?

No; there is so much more to being a good lawyer than what you learn in law school. And so, I really needed to be mentored and with some people that were more experienced, who could in turn teach me the ropes and help me understand, you know, what you did as a good lawyer. So, I ended up giving it up and getting a job with Wally Fujiyama’s law firm. He established himself, even on the national scene, as a very accomplished trial attorney. But you know, Wally, for all his success as a lawyer, never forgot his ties to the community. And I think that for him, that was an important—he saw it as a social responsibility that he bore to not just focus on his own law practice and pursuing opportunities for himself, but also to contribute to the benefit of the community in terms of, you know, the lives of other people. The other thing about him that I thought was really admirable was that he was a risk taker. And so, he wasn’t hesitant to put himself out front and to become the subject of criticism.

Do you remember that time when you were struggling to run your own place, do you remember feeling embarrassed that another lawyer saw you do something?

Oh, yeah. No; there were many times when, you know, I realized that I was over my head in terms of the assignment that I had. And it was frustrating. It was frequently humiliating.

Did you second guess yourself, saying, I shouldn’t have done this, I shouldn’t have gotten, this is not my—

Oh, definitely. No; I thought to myself that, you know, I mean, this was not the right career path. Which is why I abandoned it.

But you stayed in law; you didn’t abandon law.

No; no. But quite honestly, I hated practicing law. I thought it was a mistake to have become a lawyer, because I just didn’t enjoy it. It took me over ten years before, you know, I finally started to feel more comfortable about what I was doing, and began to enjoy it.

In 1996, Colbert Matsumoto was appointed the Court Master for Bishop Estate. It was a role that required him to examine the finances and structure of the multi-billion-dollar trust for Native Hawaiians. Within a year, the Estate came under fire amid allegations of gross mismanagement, and many called for the powerful and highly paid trustees to resign. Matsumoto unexpectedly found himself taking on the trustees in a scathing 120-page report he issued to the court.

When the judge appointed me to be the Court Master, the controversy hadn’t erupted. I knew that being Court Master for Bishop Estate was a high-profile of engagement, but I had no clue that it was gonna be as controversial as it ended up being. So, it wasn’t until almost a year after I had been appointed that things kinda erupted. The Broken Trust essay was published, the march on Kawaiahao Plaza occurred, and by then, I started to realize that, you know, this assignment that I had undertaken was gonna require that I take on the trustees. And that was kind of an intimidating notion to think about at that time. Because I had just started my own law firm a couple of years before that. And so, I actually thought to myself, you know, Okay, here I’m in this situation where if I do my job right, I’m gonna end up getting five of the most powerful people in Hawaii upset at me. So, I did think about tendering my resignation to the judge. But as I was kinda weighing that decision, I reflected on, you know, why did I go to law school, why did I want to become a lawyer. And I thought about the idealism that I had when I was in my twenties, and wanting to, you know, make a positive contribution to society. And so, I thought to myself that, you know, here I’m a positon where I could make a difference if I did my job right, and if I did it in a professional way, and am I gonna walk away from it. And so, when I looked at it in that way, I decided that, no, I should stick this out. And that’s what I ended up doing.

And what did you find? You saw the raw data, or at least what raw data was presented to you.

Well, I found a lot of issues with respect to accountability and transparency. You know, a lot of the investments that they had engaged in were not going well, were not performing as they should have. The other thing that they had done was, they had divided up areas of responsibility among the five of them, so that each of them basically had control over a different aspect of the estate. Which I found to be a violation of the trust that had been given to them, because Princess Pauahi had basically designated that there were five trustees that were all supposed to act in concert, rather than, you know, five individual trustees—

Five CEOs.

–that had their own kuleanas, and could make decisions that would be unchallenged within their kuleanas. And so, you know, that was part of the governance of Kamehameha Schools that I felt were not in conformity with what the Princess’ original wishes were, and certainly not in conformity with trust law.

What was the turning point, do you think, in the legal case that really turned the trust upside down, and resulted in the removal of a trustee?

Well, things started to deteriorate over the three years that this was going on, for the trustees. And I think that they, as I said, hunkered down. They were very resistant to making a number of the changes that the court expected of them. And then, the real blow that I think did them in was when the IRS came in and raised a number of concerns about their behavior and their management of the estate.

A lot of that was based on what you had put out; right?

Yes and no. You know, the IRS had done a lot of their own homework, and they had other issues that they wanted to raise with the trustees. But you know, IRS has a very heavy hand, and when they enter the picture, you know, it’s pretty tough [CHUCKLE] to fight them.

Colbert Matsumoto ended his twenty-year legal career in 1999, and became chairman of Island Insurance. Matsumoto is known as a strategic problem-solver. He used his skills and his influence to help save the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii from foreclosure in 2002. Matsumoto led a team that successfully raised nine million dollars in just a few months.

How did you actually get the money?

Well, you know, it took a lot of hard work and effort. And so, you know, our group—and we called it the Committee to Save the Center. We knew that this was a desperate cause, and that nobody likes to contribute money to what they think is gonna be ultimately a failed effort, because you know, you’ve heard the term, you know, throwing good money after bad. And so, nobody wanted to throw good money after bad. So, what we pledged to the audience was that we would only cash their checks if we had raised enough money to save the center. But until then, all we were gonna do was collect checks. And so, that’s what we did. And I think that that gave people the confidence to contribute to us. Whenever we would receive a donation, we would do a personalized letter to that person, thanking them for their contribution. And I would sign every letter. And so, my wife would stay up with me at night to help me stuff envelopes, and get the letters ready to be mailed out to the people that donated. And so, yeah; it took a lot of work, but it was very satisfying.

When you look back at that, did you learn new things about yourself?

Not so much about myself, as much as my confidence in my community was not misplaced. It reaffirmed my sense that, you know, we are a special place, we are a special community, that you know, Hawaii is a place that retains a lot of the qualities that growing up on Lanai, I think, I felt were unique once I was able to contrast it to my experiences on the mainland. And so, it reaffirmed my desire to try to maintain those qualities about our community.

Colbert Matsumoto chose the business boardroom instead of following his parents into a labor union. However, his strong sense of community goes back to his parents’ values and the sense of extended family in his upbringing on rural Lanai. To that, he added higher education and Zen training. Thank you, Colbert Matsumoto, for sharing your story with us. And thank you, for joining us. For PBS Hawaii and Long Story Short, I’m Leslie Wilcox. Aloha, a hui hou.

My own daughters, my two daughters, when they were in elementary school, we went to Lanai for a visit, and I remember giving them like ten dollars and telling them, you know, Why don’t you go buy some ice cream, you know, from the ice cream store? And so, they looked at me like, you know, Well, aren’t you gonna take us? And I said, No, you know where it is, so why don’t you walk from Grandma’s house to the ice cream store. And so, they did. And it was the first time they had ever done that.

And you felt okay, ‘cause it was Lanai.

Oh, yeah. No, I felt perfectly fine about it. And it was definitely a new experience for them.

[END]