The PBS Hawaiʻi Livestream is now available!

PBS Hawaiʻi Live TV

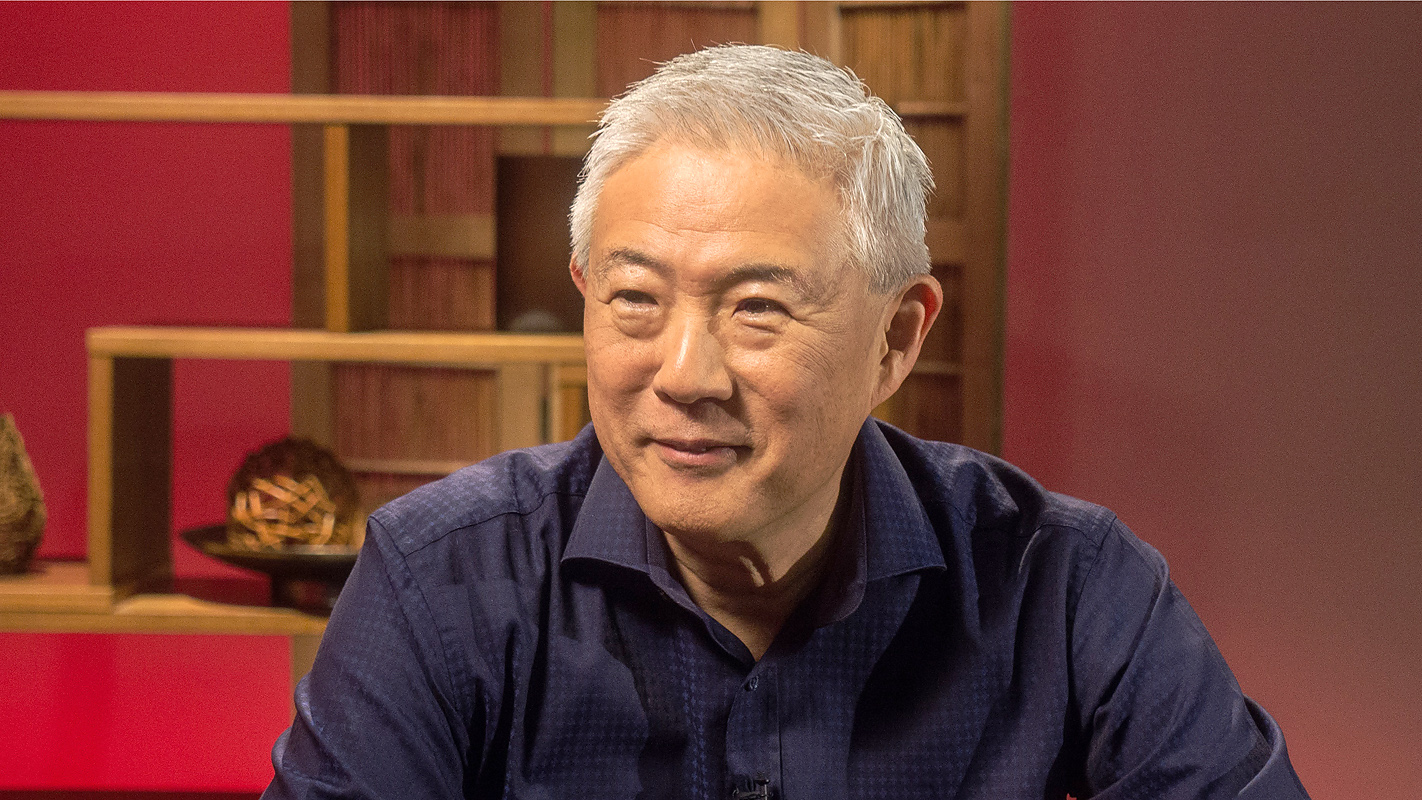

Growing up on the island of Hawaii, Glenn Furuya was raised by what he calls the “village” of Hilo. There, he learned the importance of hard work and building relationships, and saw how local values and humility helped build successful businesses. Furuya now channels these local attributes as he teaches leadership skills in Hawaii and around the world.

Transcript

We teach through a lot of protocols, rituals. It’s gotta be simple. ‘Cause I’ve come to realize that the simpler you can make it, the closer you are to universal truth. So, I play for simplicity, practical, simple. But this is really important; sticky. A lot of what happens in education isn’t sticky. I mean, nobody can remember. You can go to any one of my clients, and there’s a language out there; bowls, bananas, rocks. And finally, it has to be transformational. Why would I teach something that does not have the potential to transform someone’s life?

We’re all products of our upbringing; where we grew up, who raised us, the lessons learned along the way. Glenn Furuya has embraced his roots and his heritage, and applied them not only to his life, but to the lives and careers of leaders around the world. Glenn Furuya, next, on Long Story Short.

Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox is Hawaii’s first weekly television program produced and broadcast in high definition.

Aloha mai kakou. I’m Leslie Wilcox. Glenn Furuya has made it his business to teach others how to be effective leaders. He has presented his lessons to hundreds of businesses in Hawaii, throughout the Pacific Rim, and around the world. His distinctive style of teaching, incorporating local metaphors, nicknames, and playing for simplicity has become Glenn’s trademark. And while many of his lessons on leadership address complex situations, his practical messages are deeply rooted in the ethics of his parents and the community that raised him.

Leslie, I grew up in Hilo, Hawaii. Went to public schools there, started my career there. Went to University of Hawaii Hilo for a year or so, before transferring to Manoa. But, Hilo roots.

And what was your family like?

My father was a salesman for Fred L. Waldron & Company. He sold Kraft cheese, Kraft dressings, and he went around the island selling those products.

Did you ever go with him to see how he sealed the deal?

Yeah; every once in a while, he’d take us. But it was a very relationship-oriented type of sales. It was not, you know, hard selling. So, they all became friends, and when he’d go to these places, it’s basically taking orders. You know, and some of the stores that he’d go to were the tiny, little stores. Like, I remember one in Waiohinu, Kau. And the owner there, his name was Jack Wong Yuen, Wong Yuen Store. They became very, very, very, very good friends in the process.

Oh, that was a big circuit, going all the way there.

And like, once a month, he’d get in his car, and he’d go right around the island selling his products.

And was he a born sales guy, he loved making the sale?

Yeah; my father was more of a relationship type of guy.

So, he liked making them happy.

Yeah. And, you know, just knew how to build a friendship. And it was through that friendship that the sales came. So, that’s where I kinda learned early on about relationship selling. It’s not necessarily about the hard core type of way of doing things.

And what about your mom? Tell me about her.

My mom, was a clerk in a store in downtown Hilo. It was called Star Sales & Service. And she worked there for maybe thirty years. And in her fifties, the owner of the store passed away. And so, my mom decides that she wants to start her own store, so she started a little, small store. My mom had a passion for things Japanese. So, she created a store called Panda Imports. It was like a mini, mini Shirokiya.

Oh …

All Japanese products, food, music, et cetera. And my mom, she didn’t graduate from high school. Very intelligent woman, became very successful. She ran the store successfully for over a decade before she passed it to my brother. Hilo was a very, very interesting place to grow up. You know, very, very humble beginnings. A lot of the beginnings were in sports. Leslie, I lived right next door to the Boys Club of Hilo; just right next door. So, we were constantly at the Boys Club, playing baseball, football, shooting pool, having fun. So, a lot of my time in my youth was there. And I also was pretty active in Boy Scouts. My scoutmaster took us camping every month, so we went to every little nook and cranny corner of the Big Island, from Waipio Valley to the top of Mauna Kea.

Really outdoorsy stuff.

Yeah; yeah. So, between Boys Club and the Boy Scouts, I had a fun youth.

It sounds like a lot of relational stuff, like your dad did.

Yeah. I think when you grow up in a small town like that, where everybody knows everyone … I’ve always believed that behavior is a function of social and systemic context. So, I grew up in this context that sort of shaped my behaviors, but if you look at Hilo people, we’re pretty similar. There’s a way about Hilo people. And I was very, very blessed to be brought up in that environment. So, it was a place where I had to behave myself, because if I didn’t, before I got home in the afternoon, somebody was gonna call my parents, and then I would be disciplined [CHUCKLE] for having done whatever I did. So, it was this very interesting place.

The village raised you too; right?

It was the village that raised us in Hilo.

There’s one expression you use, and it’s very traditional, and it goes back generations in your family. And many Japanese families have this as something that guides them.

M-hm.

What is that?

I believe it is this concept called okage sama de; I am who I am because of you. And I really believe in that, that because of my parents and the sacrifices they made the discipline they gave us, the love that they extended, I think that made me who I am. But my grandparents also set a phenomenal example for me of hard work, diligence. You know, okage sama de. My father is a crusty, old Japanese man; he was more of a disciplinarian. He spent a lot of time with his friends, but my father, I am extremely, extremely proud of. He never really expressed much love, but he was a member of the 100th Battalion. And you know, if you think back to the prejudice, the hatred, the discrimination against people of Japanese ancestry because of the Pearl Harbor situation, and yet, these young men at that volunteered to fight for the American army, and all this hatred, and their families are sent to internment camps.

And everything was taken from them.

Everything taken from them, and yet, they had it in them to go to war, fight for America. And they come back the most highly decorated military unit in entire United States military history. There are two words that I really—another Japanese thing that I learned in my growing. One word is the word gaman; the other word is ganbatte. Those two words. I have little rocks on my desk, and one is gaman, one is ganbatte. Gaman is just, whatever happens, you just gotta be strong; you just gotta suck it up. You just gotta be patient. Ganbatte is, man, whatever you gotta do, you just go for it, man, just full-on move, go, get it done. You know, my father’s group; they exemplified those two qualities. Gaman; all that prejudice, all that hatred, right? Called names, and yet, they sucked it up, they said, That’s okay, we’ll show these people we’re Americans, and we’ll fight for America. Then they pulled out the ganbatte, go for broke and come back the most highly decorated military unit in entire United States military history.

And your father was one of the very decorated. What did he win as a medal?

Well, he wasn’t highly decorated, but they recently were awarded a couple years back the Congressional Gold Medal. You know, because of that okage sama de, I am who I am—I don’t want to sound like I’m bragging or anything, but I always had this thing in me that whatever I did, I just wanted my parents and my grandparents to just be proud of what I did, in whatever I endeavored to do. I’m sorry, but that was kind of the driving force in my life.

Whether they were alive to see it or not?

Yeah, yeah. Right. Just do what you can to make ‘em proud.

For Glenn Furuya, the road to doing what you can to make ‘em proud started on his family farm, preparing for a career in agriculture. But Glenn realized that his heart wasn’t in it.

Did you have a sense of what you wanted to do when you grew up?

You know, it was an interesting journey. I really didn’t have a real clear idea. We had a family farm; my grandparents, who came from Japan as immigrants, were able to buy eighteen acres of farmland, so they had this farm, and every weekend, we’d go there and work on this farm; mac nuts, et cetera. You know, hard work. So, initially, I thought maybe agriculture, go into agriculture, become a horticulturist or something like that. Um, but then …

That cured you. [CHUCKLE]

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Working on the farm.

No; what cured me was my first year of college, I took this horticulture class, and then we had to grow plants, and there was vermiculite and whatever things are that you grow plants in. And we had to go care for ‘em on weekends and things, and I just didn’t like that. And I also had an issue; to get a degree in agriculture, I had to have a foreign language. And I just couldn’t pass second year German; it was just too hard. So then, I had to kinda maneuver and figured, okay, what am I gonna do? So, I decided to switch my major to education, and got my degree in ed.

You are in education now, but a different kind of education. How long did you stay in the Special Ed education?

I was there for eight years. And those were very good eight years. You know, today, I work on leadership, I teach leadership today, is what I do. And those eight years taught me how to lead. That was a very, very interesting experience. I challenge all the people that I work with; try it sometime. You know, just try it for one hour; special ed classroom, sixteen kids. And in those days, it was self-contained; it was kids with mixed disabilities. And you’re in this room all by yourself.

I can see it as a lesson in management.

Oh, absolutely.

But leadership, you’re saying?

Yeah.

Which is different.

Yeah. I think there were two elements there. Classroom management was number one. You had to keep these kids in order, clearly defined rules, people following the rules, managing that environment. The leadership came through the requirement to inspire these kids. You know, these were seventh, eighth, ninth graders; they came from disadvantaged communities, most of them single parent homes. They couldn’t read, they couldn’t write, and you know, defeated in the spirit. And the leadership part was to try to encourage these kids, inspire them, to just give them some hope that, you know, life can be good for them, and they can find success.

How did you do that?

I felt that the greatest gift I could give these kids … and it was not easy to deliver this gift, was to teach them how to work. Because unfortunately for many of them, they’d end up in the kind of labor jobs, custodial job, you know, the simpler clerical jobs. So, I figured if I can help them and teach them how to work, and how to be a good worker, they could sustain themselves, you know, through a career. Those days, there was a lot more flexibility to what teachers could do in the classroom. And I decided that, you know what, if I’m gonna teach them to work, I need to have a business within which they could work. So, my classroom was right next to the teacher parking lot. So, I thought, I know what the business is gonna be; I’m gonna have these kids polish the teachers’ cars, form a business, and charge the teachers for polishing their cars and cleaning and vacuuming; right? It gave me an opportunity, therefore, to have these kids be a participant in an organization. They could learn things like customer service, productivity, quality of work.

And there’s detailing and then, there’s broad-brushing.

Absolutely. You know, teamwork. But the way I set it up was—and this was part of the management side of the equation. In the mornings, if they studied hard, they followed the rules, they behaved themselves— ‘cause there were a lot of behavioral issues. Okay? Then, they could go out in the afternoon when the classroom got really hot, and work in the car polishing business. And they all wanted to get out of that classroom. They they actually liked polishing cars. [CHUCKLE] So, I’d take the proceeds and I’d reinvest back in the kids. So, we would go camping, we’d take them to Special Olympics, we would give them treats, we’d even do steak fries. Right in the middle of campus, we’d cook steak, and the the whole school could smell the steak. We had so much fun.

While Glenn Furuya was working at a special education teacher, he also worked part-time at KTA Super Stores, a locally owned grocery store on Hawaii Island. At the time, KTA was beginning a period of transformation from a small country mom & pop market to a modern day supermarket. Glenn found himself in the middle of that transformation.

After eight years, I left. I went to the market, KTA Super Stores, grew up in Hilo, and I went there to work fulltime.

What did you do there?

I was sort of an assistant to the president. I worked for a very, very enlightened leader there. His name was Tony Taniguchi. And he was just a remarkable, remarkable man. And I was sort of an executive assistant type person. He allowed me to facilitate the meetings of the executive team, I ran advertising, kinda participated in the strategy.

And you had a lot of leeway?

Yeah; he gave us a lot. Tony was the kind of leader; he would give us an assignment and give us some space to do what we had to do. Very encouraging, but he’d also invest in us. He gave me an assignment to work on developing supervisors, but he told me, You know, go to whatever training you need to go to. He also told me, You gotta join Jaycees, though, and you have to join Jaycees ‘cause they have these courses in the Jaycee movement where they teach you how to lead. So, I did all those things. I have a lot of aloha for Tony; he did so much for me in my career. I started to think about in my head, this duality. In the market, I was learning systems, and how important systems were to transform an organization. Okay? ‘Cause you had to have systems to deliver the results. But in the classroom, I had to really understand how do you engage people who hated you. They didn’t want to be there, they were somewhat disgruntled, and they were defeated. They had defeated spirits. Then it dawned on me; what if you could create an organization that did both, that had systems that could transform it, like we were doing at the market, but you really knew how to take care your people in the process. What if those two forces came together; what would happen?

Were there examples of businesses that do that?

At that point, I started to research a lot. And one of the first books early on that came out was this book, In Search of Excellence. The first attempt to try to define some of the patterns of the most successful companies. And I began to read these things. I says, Wow, a lot of the patterns I’m seeing show up in this book. So then, I started to read, like read a lot, just research a lot, trying to figure out these patterns, will they work? It ended up in a mantra that I came up with. The mantra was, if you want results, systems make it possible. People make it happen, though. You still need people. Somebody’s gotta do the work. The third element I discovered was, leadership is the key. Leadership is what pulls it all together. Because leadership develops the system, and leadership has to grow the people; right? Without those two, it won’t work. So, that’s where my initial thrust came from, you know, philosophically and theoretically, from that combination of elements.

I feel a move coming from KTA Super Stores.

[CHUCKLE]

So, you left the stores at that point to develop your leadership practice?

Yeah. I spent two years fulltime. I left teaching; I resigned. Went to the market for about two years, and then—this was thirty-three years ago, I left the market and went to start my own consulting practice. Which I’ve been very, very blessed with wonderful, wonderful clients. Large companies, small companies; these are special people. I owe everything to them.

By now, Glenn Furuya had learned lessons from his parents that had been passed down through generations. He’d observed how the residents of Hilo worked and communicated with each other, and

saw how a business could grow through his experience with the late Tony Taniguchi. It was time to share what he’d learned. In 1982, Glenn Furuya founded his own consulting company, Leadership Works.

The way I teach it is this. There are two types of leaders, Leslie. There’s circular leaders. These are people are who are very collaborative, they’re relationship-oriented, they’re kind, they really engage people. Circular. Island people are generally more circular. Okay. And that’s because in Hawaii, we’re a three-way blend of cultures. We are influenced heavily by Eastern culture, ‘cause in the 1940s, forty percent of the population of Hawaii was Japanese. So, heavy bushido code influence here. And yet, we’re all Americans; that’s the Western influence. We’re all Western-educated folk. But at the same time, the host culture here is Hawaiian. We have a major Polynesian influence. And there’s no place in the world these three forces come together like it does here in Hawaii. So, the Polynesian and the Eastern, Asian, right, give us the circular. We understand circular; that’s why people are so collaborative and warm, and aloha spirit, and ohana. Western culture is much more linear. You know, there’s the goal, here’s the plan, now do it.

And if you have to run over somebody to get there, it’s okay.

Right.

‘Cause that’s the goal.

Right. So, in answer to your question, a lot of times … and there are a lot of island people who are just very linear, too. The biggest mistake you can make in Hawaii is take your linear approach, and slam it on the circular. Right? And then, that equilibrium gets broken. Who the heck does he think he is?

We’re talking as if leadership is a position. But it doesn’t have to be.

You know what I say? It’s more of an essence. It’s about being fundamentally a good person with solid values. It’s more almost like a way of life, and you gotta live it first. We always emphasize in our organization or at Leadership Works, you gotta be able to lead yourself first. And if you can’t lead yourself, you cannot lead anybody else. We always teach it this way. That life will present you hot water; boiling hot water is like difficulty, problems, trouble, pain. It’s whenever hot water comes your way, you have three choices. If I took a carrot, a raw carrot, and I put it in the hot water, and boiled it for fifteen minutes, it’ll come out soft, mushy, break apart; right? Is that who you are as a leader? You going be a crybaby, a whiner. There are a lot of crybabies out there. Second option; take a raw egg, put it in the hot water, fifteen minutes bubble and boil. Pull it out, hard-boiled; right? Second option in life; you can be an angry, bitter person. You can go yell and scream at people; second option. So, what we try to teach is that you have a third option. What if, in the hot water, you put some tea? Just like your tea there.

[CHUCKLE]

And stir it up, and all of a sudden, the hot water became a flavorful drink. We call it flipping. You gotta flip it; right? You go make tea.

Are you a carrot, or an egg? Or can you be a cup of tea? A personal tragedy in Glenn Furuya’s life made him look at his own life through the lessons he had shared with so many business people.

Let’s talk family. You mentioned your wife is your business partner. Can you tell a little about family stuff with you?

Oh, family things. Yeah; I have, actually, two families. The first family was from my first wife, who unfortunately, passed away from cancer. So, I have three adopted kids from Kathy. And my second marriage with Debbie, I have the one child I talked about who works on Wall Street today. So, that’s the family. I have three grandchildren; one here in Honolulu, Kiki, and two in Texas, Elijah and Kaila.

Did your first wife die at a young age?

Yeah; she was in her fifties. That was quite tragic. She was a teacher for almost thirty years. Very hardworking, good woman, and went to the doctor, found out there was a tumor, ovarian cancer, and passed about a month after that.

Wow.

So, you know, it’s very interesting, Leslie. Like, as I teach many of these concepts, I kinda can personalize them. Like, remember the hot water?

M-hm.

That was hot water, man. That was like, painful, and that was hard. But three choices; right? I can be a carrot, I can be an egg, be angry at the world, angry at God, angry at the docs. I could turn into a depressed crybaby, or flip it and go make tea; right? And so, you notice people always criticize clichés. In my opinion, you know when you’re in the moment and you’re struggling, the cliché comes in really helpful. ‘Cause I kept telling myself, Got three choices here. Which choice you’re gonna pick?

You sound like you’ve had some really interesting life experiences, too, having three adopted kids. Are they related, or are they separate adoptions?

Yeah; separate adoptions. Two from Korea, and one local.

Babies, you adopted?

Yeah; they were young, they were very young. I think the oldest that came was maybe about nine months. The rest were like, two and three months.

So, it really makes you stop and think of what is family, and choosing family.

Sure; absolutely. Yeah.

And then, of course, when someone passes away …

Yeah.

You don’t have the right of choice.

Yeah, yeah. No; it’s tough. So, you know, there’s still ramifications from Kathy’s death. I mean, people grieve in different ways, and you know, still struggle with some of the fallout from that. You know. So, it’s not been easy. That’s the thing about my job. It’s hard sometimes, because you try to teach people the right way to do things, you know, I’m not perfect; I can’t be this perfect, god-like person.

You don’t feel very inspiring when you’ve just lost your life partner.

Yeah, yeah. It’s hard, and so, you know, you’re gonna break down, you’re gonna react in maybe sometimes negative ways. And so, sometimes, you feel like a hypocrite; right? And so, that’s the hard part of the job, ‘cause I am not perfect. I don’t do all these things that I teach, I fail many times at home, and with the kids. But you know, you just gotta get back up and keep moving along; yeah?

Well, that’s the authentic part you were talking about.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. But it’s not easy. Life is not easy at all, you know.

And you did remarry.

Yes. Got remarried to Debbie, who really, again, has made a big difference. Yeah.

While Leadership Works is a business, Glenn Furuya takes his job personally, and takes the most pride in how his simple ideas have changed lives.

Back in our office, I have, I think, eight binders; thick, thick binders. And they have page protectors inside. For the thirty-three years I’ve been doing business, I saved every thank-you letter, thank-you email, thank-you card I ever got. And it’s like stacked full, eight binders full. So, if I ever get discouraged and think that our work isn’t making a difference, I go back to this binder and read the poignant stuff in there, man. Like, whoa. A couple days ago, Debbie looked into, I think it was Yelp, to see if anybody ever Yelped us; right? And she found an entry. And it was from a young woman named Carly Tsai, and and she wrote how the course really transformed her life. And Carly is a really cool young woman, came to class, was just totally focused. I wasn’t sure if she was getting it, because she was just so, like, focused; right? But later on, I talked to her mom, and the mom told me how Carly really changed, and other people have told me that it really made a difference. And then, she gave me a personal testimony. So, it’s not me, Leslie; it’s just that after forty years of collecting this wisdom and sharing it, I know the stuff works. It can help people. It can change lives. And so, Debbie and I are dedicated, along with our third part of our triangle, Terry Uehara, and we work very closely together to continue to just share this information. Because we know it can help people.

In 2012, Glenn Furuya received the Kalama Award from the Rotary Club of East Honolulu for inspiring excellence in business, and service to the community. When Glenn received the award, he accepted it on behalf of his late mother for teaching him the true meaning of giving and service. Mahalo to Glenn Furuya for sharing his story with us; and mahalo to you for joining us. For PBS Hawaii and Long Story Short, I’m Leslie Wilcox. A hui hou.

For audio and written transcripts of all episodes of Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, visit PBSHawaii.org. To download free podcasts of Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, go to the Apple iTunes Store, or visit PBSHawaii.org.

My grandparents were all Buddhist. And at every funeral, they’d read that White Ashes piece. Though in the morning we may have radiant life, in the evening, we may return to white ashes. So, it’s about the impermanence of life, how life is very transitory. It just so hit me, hearing it four times when you’re at a funeral; you’re all sad, you hear the White Ashes being read. It made me realize, we only got one shot here. We got one shot.

[END]