The PBS Hawaiʻi Livestream is now available!

PBS Hawaiʻi Live TV

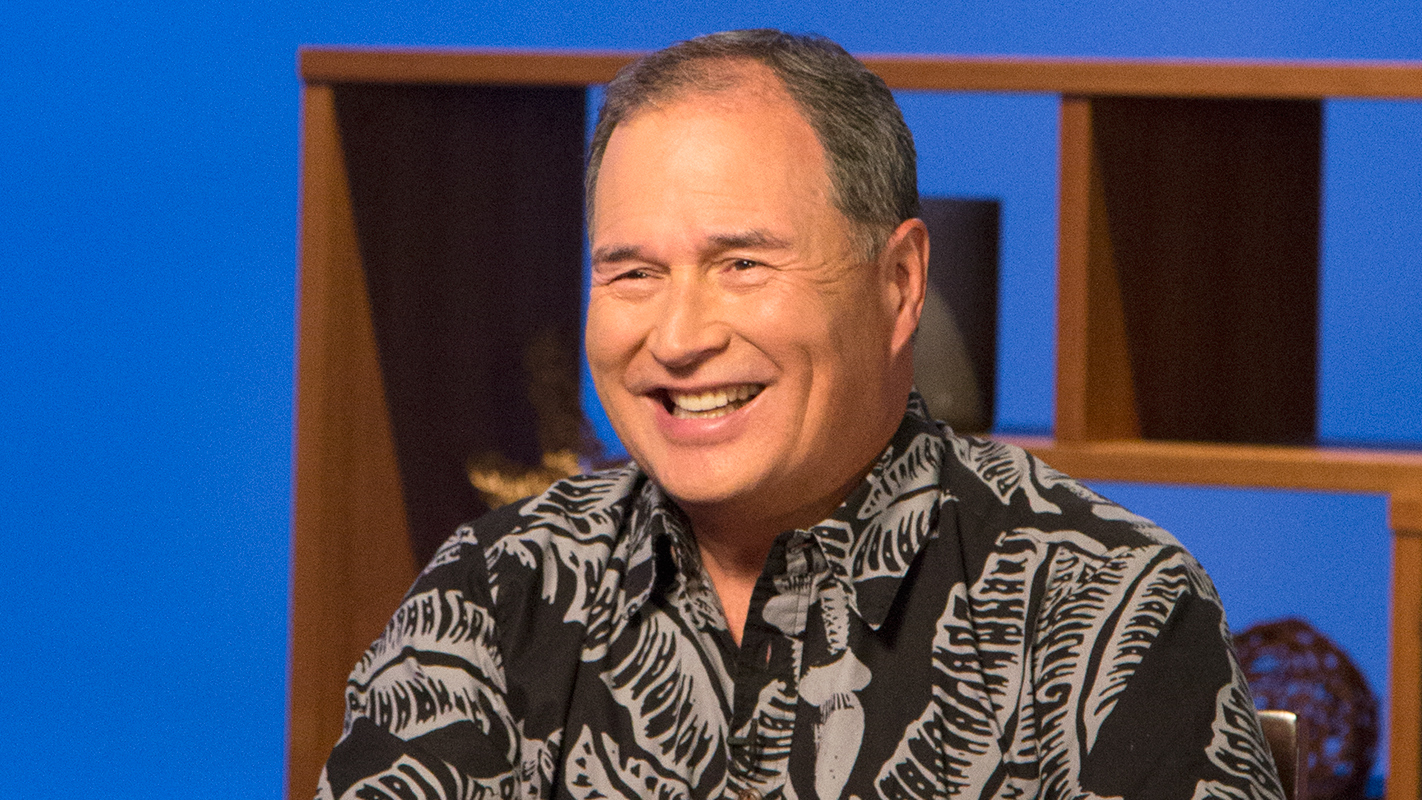

The next LONG STORY SHORT features Mike Irish, known as Hawaii’s “kim chee king.”

As a young man starting college, Mike broke his neck in a football impact which

left him paralyzed. He had to leave college and faced the prospect of never walking

again. However, he never gave up hope – and somehow he regained full movement.

Perhaps as a result of facing down his fear, Mike lives with a sort of fearlessness

which has helped make him a successful Honolulu businessman. You’ll hear how

risk-taking helped him develop an unconventional business model and enabled

him to corner the market in legacy local food brands.

This program is available in high-definition and will be rebroadcast on Wed.,

May 20 at 11:00 pm and Sun., May 24 at 4:00 pm.

Transcript

Have you ever been broke?

Oh, yeah. Yeah. I have; many times. Many times.

You’re serially broke. [CHUCKLE]

Yeah; yeah.

But then, you always gain your money back?

Yeah; mm.

Are you comfortable with that? How comfortable can you be with that?

You know, we came from nothing, so nothing doesn’t scare me. Everything’s been the outside, so our family was very poor at one time. So, coming from that side, having nothing, it doesn’t scare me.

Mike Irish has been battling the odds throughout his life, but has found success as a real estate developer and as the Kim Chee King of Hawaii. Owner of Halm’s Enterprises and other businesses, Mike Irish, next on Long Story Short.

Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox is Hawaii’s first weekly television program produced and broadcast in high definition.

Aloha mai kakou. I’m Leslie Wilcox. When life knocks Mike Irish down, he gets right back up again. When he broke his neck and became paralyzed as a young adult, he somehow learned to move and walk again, amazing the doctors. And when they warned him to restrict his physical activities, he lifted weights, bodysurfed, and entered triathlons. This fearlessness translated into Mike’s approach toward business. When he nearly lost everything in several business ventures, he continued to risk it all, and found success as the owner of Halm’s Kim Chee and other favorite local food brands. Growing up in the neighborhoods of Liliha and Kaimuki, Mike was introduced to the entrepreneurial spirit at a young age.

Tell me about how life began for you. Where, and what was your family like?

Mother, Korean; father, Caucasian.

And part Irish?

Oh, yes; part Irish, English, Scotch, Dutch, German. And Queen’s Hospital, and raised for the first five years up in Liliha. And then, moved to Kaimuki up by Leahi Hospital. And that’s where I went to Liholiho Elementary School, Kaimuki Intermediate, and then Kalani.

And what did your parents do? What were they like?

My father was a entrepreneur; he was always doing business. He got into general contracting and developing. My mother was more of a stay-home mom. There were six of us. They each had a child coming to the marriage, and they had four of us in the marriage.

How many boys, how many girls?

Three boys, three girls. And it goes, boy, girl, boy, girl, boy, girl. And so, I’m the youngest boy.

She had a business, as well.

Yeah. I don’t know if she had the business as well as my dad wanted her to have a business. ‘Cause he loved business, too. So, he got her a little ice cream parlor in Kapahulu called Dot’s. ‘Cause her name was Dorothy. And so, they called it Dot’s, and everything was dots; right? And the tablecloths and so forth. So, we did that for, I think, about a year or two.

Did you help out?

Yeah; I’d go down, and I’d take all my pay out in ice cream. [CHUCKLE]

And she paid well; right?

I think that’s why she ended up closing about a year and a half later. [CHUCKLE] All of us came down and ate more ice cream than we sold.

Did she like doing it, even though it wasn’t her idea?

Yeah, she did. You know, I think she wanted to experience that side of business, to get a feel of what it feels like to not be able to sleep at night, ‘cause you gotta worry about all these different things, rather than just getting up in the morning. She was a maid at the Moana. And so, this was a little detour from that.

Were they the kind of parents who would sit you down and give you advice, or did you learn from them by watching?

You know, what’s really funny is that by the time I was five going on to six, they actually got divorced.

Oh …

But it wasn’t like divorce, where the father was not connected. You know, he would always come by, and if we ever stepped out of line, she would call him to come home and straighten us out. And we’d spend the weekends with him, and so forth. And what happened when I was about thirteen at my ninth grade year at Kaimuki Intermediate, my mother passed away.

How old was she?

She was forty-one.

Oh, my goodness.

Yeah.

So, you had a lot of loss early.

Yeah; yeah. So you know, it was pretty tough, especially on us at that time.

Where did you go to live; with your father?

No, actually, he moved back into the house. But then, it’s a little different, you know, ‘cause you’re being raised by a Korean mother, right, who’s very—and then—

Who’s very, what?

Who very much takes care of the boys. [CHUCKLE] And then, all of a sudden, your father comes in, who’s Caucasian, and you know, everything’s fifty-fifty. We’re all doing dishes, laundry, and it’s all new to us. And so, it was really tough. There was a little bit of rebellion there.

On your part, or everybody’s part?

Everybody. First of all, the family’s hurting. Everybody’s trying to find their own place. And you know, we just tried to find other areas. So, we would get into a little trouble, you know. And that was just the way it was at that time.

And did the rebellion stop by the time you ended high school?

Yeah, I think it did. I think as you grow up, you find out that, you know, this is not what Mom would want us to do.

What were you doing, anyway? I have to ask you in particular, what’s a little trouble?

Oh, well, you know, what happens when you have that much loss, you know, you have a lot of pain. So, you go out and you’re in Kaimuki and so forth, so you get into a lot of fights and so forth. And it kinda feels good to have someone else hit you and feel a different type of pain. So, you get into a lot of fights.

And for no reason? You picked the fight?

Well, you can pick ‘em, or they’ll pick you. You know, everybody’s territorial at the time. You know, this is our block, or our area, you know, in Kaimuki. Imagine that; in Kaimuki.

As Mike Irish graduated from Kalani High School in Honolulu, his athletic talent landed him a college scholarship. However, his life was about to take another unexpected turn.

I was fortunate; I got a scholarship to University of Hawaii to play football. And freshman year, and it’s like we’re two to three weeks into the season, and it’s the last day before the day of the game. Now, we’re fourth, fifth string, so you know, but if we played well, we might be able to get suited up for the game, just to go run into the stadium. So, everybody’s playing pretty hard. And in those days, they taught us how to hit with our face, facemask in the numbers, which is now illegal.

But you were actually taught to do it.

We were taught to do that. And it was a great way to—I mean, you could really hurt somebody, or get hurt, as I found out. And that’s what happened. I ended up hitting someone, and it broke my neck. And so, I was paralyzed from the neck, down. And I thought it was a stinger. I thought, you know, it’s one of these things you shake off. And when I got to the hospital, I said, you know, Guys, I got a game tomorrow; is there something we take? You know, ‘cause I’m waiting for this thing to wear off. And that’s when the doctor told me; he says, You should be grateful you’re even alive. According to the x-rays, you fractured your number one vertebra, which means, you know—

Where is that? Which one is it?

It’s the top.

The top one.

It controls breathing, and everything. And it’s amazing that you’re still alive. I said, Okay. And that was the good news. The bad news was that you’ll probably never walk again. And I said, Excuse me?

Devastating.

Yeah. He says, You’re paralyzed from the neck, down, but you’re alive. Why would I want to be alive? [CHUCKLE] Paralyzed from the neck, down; why would I want to be alive? So anyway, about three months after the injury, they sent me to rehab. I went to rehab about two and a half weeks after they stabilized me at Queen’s, and then I went to the rehab.

What had gone through your mind, those two and a half weeks?

Oh, in the two and a half weeks, you go through … you—you refuse to believe, so you’re still on this—you know, I’m not real depressed yet. I’m just a little scared, but the mindset is that, I’ll get over this.

Yeah; I get over everything.

Yeah; right. And so, they didn’t even bother to do the surgery on me. They just put me in a halo and moved me to rehab. And at rehab, for some reason, my feeling started to come back. And after about three months at rehab, I actually walked out with a walker, but then went back to Queen’s for the surgery.

Do they know why your feelings came back? Were you working out?

No; No, they never knew how damaged; they can just tell by how I was at that time. The technology in ’71 isn’t as what it is today. But in ’71, they looked at me and just said, You paralyzed. And then they found out that maybe one out of a million might come out of this. And I guess I was just fortunate. So, that makes me even enjoy life a little more every day.

No kidding. So then. you went into surgery to fuse—

To fuse; they fused number one, two, and three vertebras. That’s why I have a lack of mobility in my neck. But I’ll take that over—

You can’t swivel your neck?

No; no.

Oh …

Yeah.

But everything else came back?

Yeah; everything else came back. Yeah.

And that was how long after?

I went into a body cast, everything. It took about two years.

Two years, you were sidelined.

Yeah; yeah.

And then, no football scholarship after that.

No; because in those days, it’s not like today. If you got hurt while you were on scholarship, the school has to pay for your school. Over there, you know, you have a semester scholarship. If you do well, make the team, you get—you know.

Yeah.

So, evidently, I didn’t make the team. [CHUCKLE]

Wow. How did that change you, do you think?

Well, you know, it just makes you appreciate a lot of things. You know.

It could have made you bitter.

Yeah.

I lost my chance at school. ‘Cause you didn’t go to college after that.

No, I couldn’t.

You didn’t get bitter? And what about friends; did they hang with you?

Oh; I tell you what. It brought so many friends to me.

Really?

I mean, Kalani dedicated a game to me. University of Hawaii had a game dedicated. They gave me the team footballs. I mean, the support, you know, so much there that, that kept me going. And once I was able to get well again, you know, I couldn’t thank all those people that were supporting me enough. In fact, that’s why today, I sit on the um, rehab board. That’s one of the reasons. I said, If they ever ask me to do anything, I’ll do it. And about ten years ago, I think, they asked me if I would sit on their board. I said, Absolutely.

After his injury and stunning recovery, Mike Irish turned his attention to real estate development, something he dabbled in from a young age. Really young.’’

Oh, my plan was, I thought I’d go to college. But I always thought I’d be this big-time developer, you know, like the Chris Hemmeters and all these guys. And that was my dream.

Because you wanted to be a negotiator, or you wanted to be rich, or all of the above?

I loved real estate ever since I was a kid. I was involved in real estate ever since I was like, eight or nine years old.

With your father?

No; actually, I bought my own piece of real estate.

You did?

Yeah. My dad sent me, ‘cause he kept getting harassed, to this seminar at the Hilton were you get steak and lobster, and you just listen to the show. And it was for lots to buy in Florida. And so, I sat there, and I was just amazed.

And how old were you? Eighth grade, you said?

No, no, no. I was eight years old; eight or nine years old.

Eight?

And I was always selling; I was always doing something. I was always trying to make money, according to my family.

What did you sell?

I’d sell newspapers. You know, I was selling newspapers when I was four or five years, ‘cause I watched people make money selling newspapers. So, I’d sell all these newspapers, not knowing that they were three weeks old.

[CHUCKLE]

‘Cause you don’t know that. Would you want to buy a paper?

[CHUCKLE] Oh, you cute little boy.

Yeah.

Of course, I would.

Yeah; that’s exactly how it worked out, you know. So, I ended up buying a couple lots, and my father had to co-sign for me. I thought, This is interesting.

How could you afford them? Had you saved money?

Oh; oh, yeah. I worked on the weekends at Chinatown, you know, the Yama brothers, a food stand, and then would work five in the morning ‘til five in the evening on Saturdays, and five to two on Sundays. And then, they’d pay you maybe between nine to eleven dollars. And then, so I knew I had like forty dollars a month. And then, during the summers, I’d work construction for my dad’s company.

And then, you didn’t blow it; you saved it.

Oh, no; what did was, actually, I made payments. I had a mortgage. I bought two lots for twenty-five dollars down; each lot, twenty-five dollars down, twenty-five dollars a month, for twenty-five hundred. So, I bought two of ‘em. And then, about three years later, I got a call. And so, now I’m twelve, so I’m already all grown up.

[CHUCKLE] Your voice is getting deeper.

And so, they asked if I’d like to sell the lots back.

Were they surprised to hear a twelve-year-old on the other end of the line?

No; my dad just gave me the phone and says, You gotta talk to my son. You know. ‘Cause I was on title, but he was my co-signer. So, I heard this, and they said, So, we’ll give you five thousand for each one of your lots. I said, What about the three years I’ve paid the twenty-five dollars? He says, Okay, we’ll give you that back too; will you sell? I said, Sure. A year later, they announced Disney World.

[GASP]

But it was okay, because I made my money back.

That’s good; that’s great.

And what we did was, we took that money, rolled it onto some land on the Big Island.

And then, what’d you do with that?

Actually, that became the downfall. Because my dad was a developer and constantly, he always risked everything, and he ended up going bankrupt. And because he co-signed and had to own that land, that land was part of his bankruptcy when he filed.

Oh; how old were you then?

Now, I’m probably like nineteen, twenty.

[INHALES SHARPLY] Oh …

But it was okay. You know, because it really was money that, although I made, you know, it’s paper.

While Mike Irish was a struggling real estate developer, an unexpected business venture presented itself. Mike then made a risk-it-all decision that would lead to success in a very different type of industry.

I worked for my father’s company, and found out how he bought and sold real estate, and so forth, and how he was doing things. And it was pretty interesting. So, I think I learned more doing that than I would at any classroom.

And then, along the way, you started acquiring other kinds of businesses.

Because the development wasn’t going that well.

What year was this?

We’re going now from about ’80 to ’83, ’84. And I tried to do development full time. And I got caught at the wrong time, where interest rates were just skyrocketing.

Oh, going nuts.

Eighteen percent and so forth. And so, I got caught up in that. And then, I bought this Parks brand products, because I wanted a cash flow business, a little business that could cash flow. And so I bought this Parks brand products, which I had no knowledge of; food. They made sauces, barbecue sauces, ko choo jang, taegu. And I had no idea, but I thought, Oh, I can learn this. But I was losing everything, and then I found out Halm’s Kim Chee was for sale. And I thought, Well, if I put the last dollar I have into Halm’s Kim Chee, and it goes broke, again, I’m where I started from anyway. So, I bought Halm’s, and put the two together, and the synergy started to work. So, now we fast forward thirty some-odd years. And most of the companies, they have come to me to purchase. I’ve never had to go to them. When they found out I bought Halm’s, then Kohala came. All these other different companies.

And these are local cult-like, you know, just very iconic brands.

Yeah. And it’s really funny. We keep it that way so everybody still thinks it’s still that little old lady here, or that little person on Big Island, Kohala. And we want them to still believe. And we follow their recipes to the tee. So, everybody thought, Oh, so you have the same kitchen. No; each one is made differently. And each one is unique in its own style.

And they’re all made in the same place?

They’re all made in the same place.

For that synergy.

For the synergy. And distributed for the synergies. And our buying power is stronger. So, that sort of helps it.

So, how many have you bought up, these brands that have great significance locally?

Kim chee brands, I think we have nine kim chee companies, two takuan companies, and four sauce companies in the Halm’s brand. And then we have Keoki’s laulau and kalua pig. And then, we have Diamond Head Seafood.

When these families come to you and they say, We’re gonna retire the brand or the company, is it because they can’t make it work or the family has decided not take it to the next generation?

Yes; yeah, yeah. That’s basically it. The kids have gotten up every morning at five-thirty, five o’clock, labeled bottles, had to come home right after school to pack kim chee in the garage, or in the houses. And so, the kids, they want to do anything else, but kim chee.

Yeah.

You know, they want to get as far away from, you know, having to do that.

Is it usually second generation or third generation that says, I don’t think so. Second?

Second. Yeah; I haven’t seen the first, where they made it good, they sent all the kids to Punahou. And that generation is saying, Well, no, Dad, I’m an attorney. Close it down, I’ll take care of you.

No more labels. [CHUCKLE]

I’ll take care of you. You know, don’t worry about it, shut it down, I’ll take care of you. You know. So, it comes mostly in that fashion.

So, these brands would have all died.

I think so; yeah.

Didn’t you change the packaging of it?

No; actually, I haven’t.

You didn’t?

Well, they were all glass before.

Yes.

I went to plastic. The glass was just too heavy and too hard. [CHUCKLE] ‘Cause we’re mixing them in vats, and when they’re making it, once they drop a bottle and crack it in the vat, you have to destroy the whole vat.

Ah …

So, it became … we need plastic bottles.

And was that a switch for the consumer, or did that go over just fine?

I think it went over just fine. I fought it for years. I—I really did; I fought it. I thought, No, it should be in glass jars, and you know, this and that. And then, all of a sudden, the economics didn’t work, the shipping costs, and then the taxing on the glass and so forth that we do here, then all of a sudden, the economics didn’t work, ‘cause then kim chee would get too expensive. So, I thought, Okay, let me try this with one brand. And we saw actually, a little bit of an increase in sales, because now, the parents could take it, put in their cars, and they didn’t have to worry about dropping the bag and breaking it, or something.

Did the kim chee purchases have anything at all to do with your being half Korean?

No; actually no, it didn’t. But the lady that introduced me was Korean was Chicken Alice. She’s the one that told me.

Chicken Alice?

Chicken Alice; Alice Ganhinhin. She’s the one who told me go buy Park’s brand products, because it was the secret to her Chicken Alice; she took that mix. So, she adopted me as her kid brother because I’m half Korean; both myself and my brother Bill.

Mike Irish forged a distinctive path to success in the business world, and along the way, he gained the guidance of several top Hawaii business leaders.

Do you have mentors, advisors?

I have great employees. I have some great employees. My mentors, one of them was Richard Kimi from the Hukilau Hotels. You know, I listen to a lot of people. Wesley Park is a good mentor. So, there’s a lot of people that help me, and that I listen to. Every now and then, even Walter Dods will give me advice. So, I’m very grateful for all the people that help me.

And of the names you just mentioned, has anyone given you advice that you could share?

Oh, yeah. I’ve gone to them on deals. You know, I’ve gone to Walter Dods. I’d ask him, What do you think about this deal? He said, Nope. And I listened. Okay; I don’t. [CHUCKLE]

What advice do you give people who want to make a dent in the business scene? And you know, you’ve done it your own way. What would you tell them that might differ from what maybe a business school would say?

My brother once told me; he said, You know, it’s funny, the harder you work, the luckier you are. If you’re willing to work hard, and put in the time and effort, you can do it. ‘Cause everybody looks at this, but when I was first starting, you know, you’re there at four in the morning, and you’re leaving at six at night, and you’re working six, seven days a week. So, all of a sudden, they see this, and they say, Oh, this is fun. But I go back to those days, you know, where I’m the one mixing the ko choo jang, I’m the one mixing the taegu.

And you don’t know if it’s gonna work out for you, either.

No, no. And I only have two other employees, besides myself. And I’m the one delivering and driving, and setting up the stores. And even when we bought Halm’s, I was my own deliveryman.

Imagine, a former quadriplegic is in Halm’s.

Yeah.

Mixing.

Mixing; yeah.

And carrying.

Carrying.

And lugging.

Actually, the doctors said, Well, what you have to do, you have to stay with rubber shoes, and you can’t lift anything over twenty pounds. And then, no sudden movements and so forth. But I’m, you know, from Kalani, so I went back to bodysurfing, I went back to playing racquetball, weightlifting. And I did about four or five Tin Mans in ’95 to 2001, I think it was. Something like that.

And was there anything you could have done to strengthen your neck, or that was it?

No.

Just use it?

Yeah.

Right?

Yeah; yeah. He said, Well, you know, the next time it breaks, you know. I says, Well, I didn’t think I’d get this far anyway. [CHUCKLE]

Seriously?

Yeah.

Because all that sounds like a risk.

Yeah, it is; it is. But you know, you know, if I lived a life in shelter and just said, Okay, this is what I gotta do, and I was scared of everything, I wouldn’t be able to do anything I really enjoyed. So, you know, it really becomes the quality of life. What do you want in your life? Do you want quality, or do you want longevity?

You mentioned that your father was really influential. He passed away at a young age.

Yeah.

Not as young as your mom, but he was not—

He was sixty-eight; he passed away at sixty-eight. So, I was only about thirty-three, I think, at the time, thirty-four.

Yeah.

But his buildings are still standing, like he said. [CHUCKLE]

Yeah. Your life has had a lot of loss.

Yeah, but it’s been pretty rich. I’ve got great brothers and sisters, I’ve got a great wife. You know, I have great people that I work with in our factories. And you know, I couldn’t have asked for better. You know, facing the fact that I wasn’t ever gonna walk again, from that point, I’m really ecstatic. [CHUCKLE]

What do you want in life? Do you risk it all to get what you want, or do you take the safer path? Mike Irish’s recovery from paralysis caused by a football injury helped him realize that taking risks could actually lead him to a greater measure of security and happiness. These days, Mike may not take as many financial risks as he once did, but he continues to run his company and his life with a sense of fearlessness. Mahalo to Mike Irish of Honolulu for sharing his story with us. And mahalo to you, for joining us. For PBS Hawaii and Long Story Short, I’m Leslie Wilcox. A hui hou.

For audio and written transcripts of all episodes of Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, visit PBSHawaii.org. To download free podcasts of Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, go the Apple iTunes Store, or visit PBSHawaii.org.

Is the market still there for several brands of kim chee?

Oh, yeah; yeah. I think so. Because everybody has a certain style that they like. No different than clothing.

Yeah. [CHUCKLE]

No different than clothing; everybody has a certain style that they like, and they’ll change.

[END]